The construction and demolition of buildings is an extremely material- and energy-intensive endeavor. According to data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, an estimated 600 million tons of construction and demolition debris was generated in 2018. (Learn more at bit.ly/31b2r8Z.) That’s more than double the amount of municipal solid waste generated in that same year.

That is an immense quantity of waste and, as the building industry looks to ramp up its efforts to combat climate change, it is calling for solutions and change. One way to help bring that level of waste down is to rethink how and from where materials are sourced and how the elements of a building are treated when they have reached the end of their life.

The idea of material salvage and reuse is far from new. Since the dawn of civilization, buildings have utilized raw materials salvaged from other buildings. For example, the Romans reused salvaged building materials in the construction of many buildings and monuments, including the

Arch of Constantine in Rome. The builders used marble tiles and other materials from other structures, including the Arch of Marcus Aurelius, which had been built almost 150 years earlier (bit.ly/3fbSqk2).

It is logical to maximize the usefulness of materials in building, particularly when you consider all the effort, energy and natural resources that go into creating those components in the first place. In the modern era, all too often we’ve ignored salvage and reuse in favor of sourcing something new. As the focus shifts to conservation, reclamation is getting a fresh look.

“In some applications, it’s both sustainable and aesthetically beneficial to reuse

materials,” says Marcy Wong, partner at Marcy Wong Donn Logan Architects, Berkeley, Calif. “Material selection is a crucial component of sustainability in design.”

Diverse Customers, Varied Needs

Rising material costs and sustainability efforts are creating a growing interest in architectural salvage and reuse, and, fortunately, there are more places to find material ready for a second life. One such source is Bellingham, Wash.-based RE-USE Consulting, which has been leading the way in the deconstruction space for decades.

“When I was at university and wanted to do an internship, someone asked if I wanted to help start a store that would basically be a used Home Depot to help keep things out of landfills,” recalls Dave Bennink, owner of RE-USE Consulting. “That was 28 years ago, and we soon realized there were more materials available if we went out and got them. We started out taking kitchen cabinets and pulling flooring from old houses before they were demolished. Then we realized we could save even more things, such as insulation and 2 by 4s, if we disassembled the whole structure. One of the things we’re most proud of is how much concrete we’ve saved. Because of the carbon footprint of that product, reusing it makes a real impact. We’ve reclaimed concrete pavers, concrete stacking blocks; we recently saved a precast concrete stair set.”

“One of the things I love about our mission and our industry is the fact that there are so many benefits that all pass through a common system and process,” adds Shannon Goodman, executive director of Lifecycle Building Center, a non-profit that sells used and refurbished building materials in Atlanta. “There is obviously the preservation of natural resources, as well as embodied carbon and embodied energy, but there is also the redistribution of economic and material wealth. Many of the people we interact with are not motivated by ‘sustainability’. They care about saving money or they like that LBC gives free materials to non-profits.”

For some communities, salvaged materials can be a game-changer. Properly recovered materials not only get diverted from landfills, but also can provide a lowercost option to those unable to afford new components.

“One of the things we’re most proud of is our diverse customer base. We have lower-income homeowners who otherwise couldn’t afford to maintain their homes,” Bennink says. “We give away insulation. We have doors that start at $9 and 2 by 4s for $1. Landlords might come in for vanity cabinets, and we have others that love the quality of old wood. In most cases, they wouldn’t tell you their priority is the

environment, but I value all their reasons equally.”

Good Work

Along with the sustainability and cost benefits associated with using reclaimed materials, proper deconstruction can provide skilled, high-paying jobs. Through an organization called Build Reuse, a national community of organizations dedicated to building material reuse, Goodman sees great opportunities for education and job training in the reclamation trade.

“We have been training people with barriers to employment in deconstruction and material recovery as a pathway to sustainable, living-wage jobs,” Goodman says. “We have partnered since 2016 with a non-profit called Georgia Works; they work specifically with men who are rebuilding their lives after experiencing homelessness or incarceration. We’ve provided over 6,000 hours of training to 60 men over the past five years and hired several as full-time employees. Deconstruction and reuse can help create rewarding and impactful jobs.”

“We train groups to do this work all over North America and a good example was when we were in Buffalo, which had experienced a mass exodus of people over the decades, leaving thousands of vacant buildings,” Bennink recalls. “Those buildings can become a blight on their communities. We came in to help a client who had a heart for unifying the population of Buffalo around their efforts. The idea was to remove the blighted buildings, hire people from the neighborhood who were unemployed and sell the materials at a low cost to those in need. The money being spent to remove those buildings, instead of going toward demolition and landfilling, stayed in the community and created a circular economy.”

Look and Feel

More architects also are looking to utilize salvaged material in their projects, ultimately achieving multiple goals simultaneously. Wong’s firm has been involved in several projects that gave buildings and their components a second life.

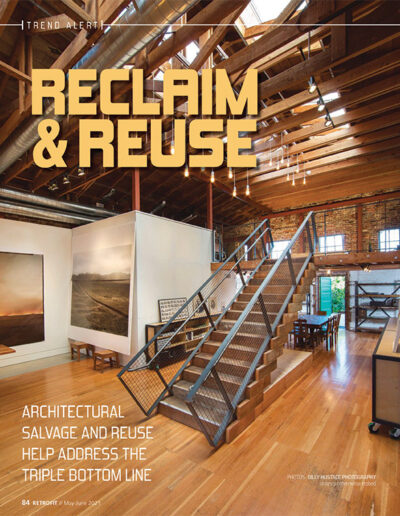

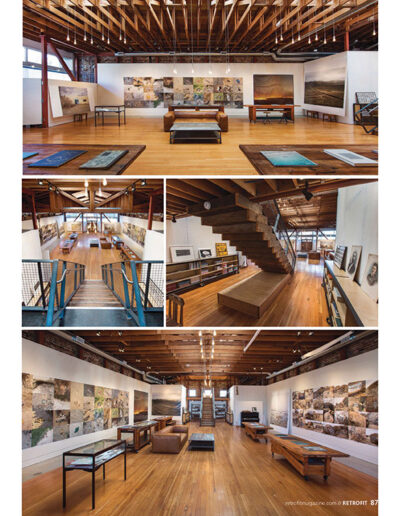

“One project in which repurposed materials are especially appropriate is the Alcatraz Photography Studio,” Wong says. [Editor’s Note: Alcatraz Photography Studio won a retrofit Metamorphosis Award in 2019. Learn more about the project at bit.ly/2qrVvVT and the Metamorphosis Awards on page 95.] “The existing building was constructed of unreinforced brick walls, wood flooring, a wood upper floor structure and wood roof framing. Working with the structural engineer and client, we designed the project to use deconstructed and refurbished structural material in the roof structural system, as well as in the newly constructed mezzanine and recycled wood stair. The fir and redwood salvaged from the original building are about a century old. They are beautiful as exposed finishes, retained by design as a testament to the endurance of wood.”

For this project, it was important to salvage as much material from the original structure for reasons of aesthetics and function, as well as sustainability.

“The use of recycled and local materials not only embraces the many positive characteristics of wood as a material, including low embodied energy, low carbon impact and sustainability, but it also helps achieve the architectural sensibility that the client and architect envisioned,” Wong says. “Recycled wood, existing unreinforced brick and new steel braces for seismic upgrading form the palette of architectural and structural materials in the project. The structure is exposed to create a spatially dramatic context for the exhibited photographic art without overwhelming it.”

“There is a wonderful project at Georgia Tech, the Kendeda Building for Innovative Sustainable Design,” Goodman says. “The project pursued Living Building Challenge certification, which prioritizes material recovery and reuse. The project uses about 10 different kinds of recovered materials.”

To support the Kendeda Building’s achievement of the Living Building Challenge, Lifecycle Building Center spent a year collecting reclaimed 2 by 4s from multiple sources, including TV and film sets, for use within exposed nail-laminated timber panels forming the upper floor and roof structure. Although the project team was unable to use the salvaged lumber for structural purposes based on local code restrictions, a strategy emerged in which the reclaimed 2 by 4s were used as spacers between the structural 2 by 6 members, which met code requirements.

“The Living Building Challenge also includes requirements tied to equity,” Goodman explains. “Only one out of 13 subs bid on the nail-laminated timber panels because they did not want to work with salvaged material, and the price of the submitted bid was too high. One of our board members serving on the project team personally organized a self-perform initiative to construct the panels in a donated warehouse on Tech’s campus, and his company, Skanska, hired six men from Georgia Works to do the work. Not only were they able to put these materials back into use, provide workforce development training and create a beautiful aesthetic effect inside the building, they were able to do it at 25 percent of that sub’s bid and save the project money.”

Reclamation Considerations

As deconstruction and reclamation techniques and technology continue to improve, the availability and use of reused materials will keep growing. There are, of course, some limitations and considerations to weigh before deciding how and where to best utilize salvaged material.

“One challenge in using repurposed or retained components is determining their structural integrity and strength, particularly when the history of the material is not fully known or the building has been unmaintained for an extended period,” Wong explains. “For example, with the Alcatraz Photography Studio project, the function and year of construction of the original building are lost to history, though it appears about a century old. The seismic resistance of the original unreinforced brick masonry walls was highly inadequate and needed reinforcement.”

While some architects, owners and contractors might express hesitation about the structural integrity of reclaimed materials, Bennink explains that it’s just a matter of downgrading.

“For example, a deconstructed bridge girder would never get certified to be reused over an interstate highway, but what about someone’s driveway?” he says. “If you’re building with lumber and the inspector says you can’t utilize used 2 by 6s, you often can use 2 by 8s. When it comes to energy, embodied carbon and resource conservation, we’re OK with things being downgraded a little if it means they are being saved and reused.”

Trends in reclamation and reuse are driven as much by supply—what buildings are being deconstructed locally and what can be salvaged from them—as by tastes and design. However, as it has with most things, the pandemic has changed the landscape of reuse.

“Since COVID started, we’ve seen increased demand in the reuse industry,” Bennink says. “It has shifted much more toward residential. People are stuck at home and want to do home renovation projects but income may be unstable. If they can find affordable alternatives and get their projects done for less money, they’ll do that. Restaurants had been a big part of our demand in the past, but unsurprisingly they haven’t been buying much lately. We predict a big boom in that sector next year.”

As technology continues to expand, with automation making salvage more efficient and effective, big data is also helping to expand awareness and availability of reclaimed materials.

“I have dreamt for years about integrating technology so you can come into a reuse center, scan a code on any of our materials and learn where it came from and what its history is,” Goodman says. “There are companies like Rheaply that are making it easier for consumers to access information about reclaimed materials. This is the big frontier: How do we make it easier for everyone to access information about salvaged materials and help them see these materials as having value instead of seeing them as trash?”

“When there are multiple benefits happening simultaneously, that’s where you get a glimpse of real sustainability,” Bennink says. “We have seen win-win-win situations where materials were saved, the environment benefitted and jobs were created. It’s a good feeling.”

LEARN MORE ABOUT MATERIALS REUSE

RE-USE CONSULTING // www.reuseconsulting.com LIFECYCLE BUILDING CENTER // www.lifecyclebuildingcenter.org BUILD REUSE // www.buildreuse.org GEORGIA WORKS // www.georgiaworks.net